How To Draw A Soccer Ball

The soccer ball has evolved pretty rapidly in the past 50 years. Most of us grew up with the soccer ball known as the "Buckminster Ball, or Buckyball," made by the American architect and designer Richard Buckminster Fuller in the 1960s.

Although soccer has been around since medieval times, the evolution of the ball itself is fun to track according to the history of the World Cup, beginning with the inaugural Cup in 1930. In the 1930 finals, both Argentina and Uruguay had a preferred ball, so Argentina's was used during the first half and Uruguay's was used in the the second. (Interestingly, Argentina was leading at halftime, but Uruguay won the match.)

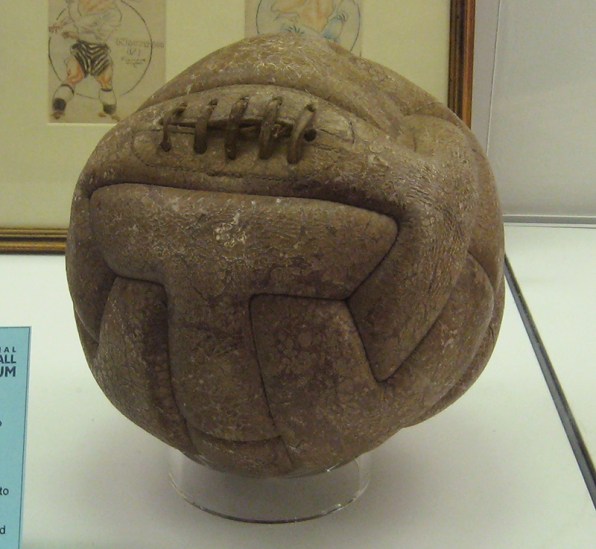

The leather used in soccer balls in the first half of the 20th century was thick, and tended to absorb water, which increased the ball's weight. That made it downright dangerous for headers–imagine trying to head a medicine ball. The heavy leather laces were also painful during headers. And inside those leather balls were rubber bladders; you unstitched the leather laces to insert them. (Check out this cool New York Times graphic, which shows what's inside the balls.) The leather became thinner and less dangerous over the first five World Cups, and the sewing pattern moved toward a standard of sorts: strips of leather arranged at 90-degree angles to each other.

By the 1954 World Cup in Switzerland, an 18-strip ball was the standard; it resembled today's volleyballs more than it did soccer balls. But it marked a major development toward making soccer balls more spherical and thus more predictable. When balls had those enormous, clunky panels, like basketballs, they often acted bizarrely. (In the 1934 World Cup, a striker scored when the ball unexpectedly swerved into the goal. According to FIFA, the striker was unable to replicate this shot the next day, even after 20 attempts.) And up through 1966, the soccer balls were all leather-colored–understandable, since they were made of leather. They were various shades of brown, tan, and yellow.

Buckminster Fuller changed all that with the 1970 World Cup, also the first time Adidas manufactured the official ball. (Adidas has made every World Cup ball since.) Fuller's ball, the classic black-and-white, contained 20 hexagons and 12 pentagons rather than the by-then-standard strips. (This pattern became so iconic that a similar-looking molecule was eventually created and named after Fuller.) The new design, with many more and smaller panels, made the ball even closer to a true sphere than the volleyball-like shape it was before, allowing for superior ball control. That let players begin (intentionally) curving their kicks, because the shape allowed for a predictable path through the air. Plus, it looked like no other ball–even now, when that shape hasn't been in use for a decade, those hexagons and pentagons scream, "soccer."

The first fully synthetic ball was used in 1986, at the Mexico World Cup, but Fuller's basic design–despite the cream-colored design of the 2002 ball, it was still a Fuller-esque pattern–wasn't replaced until 2006, with the +Teamgeist. The major development here was the reduction of the number of panels, thanks to new ways of joining the panels together. (Stitching, the classic method, is bulky and causes changes in elevation between the section where the panels are joined together and the middles of the panels.) For the 2006 ball, Adidas used thermal bonding rather than stitching, which reduces that elevation difference, again making things more spherical. New interiors of the ball–natural bladders, knitted fabrics, and foam–put less pressure on the outer synthetic material to hold the round shape, so the name of the game became minimizing the exterior material. That meant thinner material, thermal bonding, and fewer panels–which in turn means fewer seams.

This year's ball, the Brazuca, has a rougher surface and only six large panels. Adidas claims the Brazuca is more aerodynamic and easier to control than any former ball. It also doesn't look quite like any other ball in history: Its large panels are shaped a bit like the outstretched fingers on a hand, and those panels overlap in symmetrical but also wavy and casual ways. The seams on the ball are bright green, orange, and blue, and become a beautiful blur when the ball's kicked around. You can learn more about the Brazuca here.

How To Draw A Soccer Ball

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/3032101/the-curious-history-of-the-world-cup-soccer-ball

Posted by: guntergeopenceed.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Draw A Soccer Ball"

Post a Comment